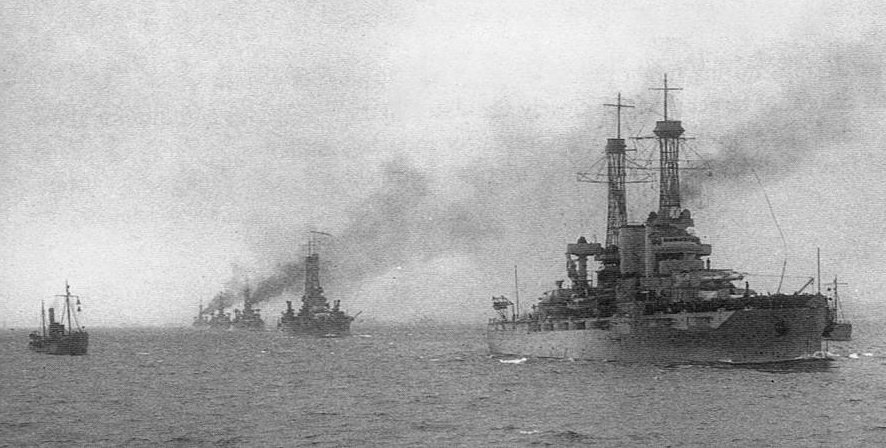

Dan Carlin in his excellent podcast Hardcore History describes the situation as follows:

“The opportunity was there for the numerically superior British fleet to apply their numbers and kick German tail, but the problem was Naval outcomes were quite variable. One lucky punch could turn the tables and in this case, remove the British numeral advantage.”

He continues, quoting Winston Churchill directly:

“The great disparity of the results at stake in a battle between the British and Germany navies can never be excluded from our thoughts.”

This “great disparity of the results” and the quite variable outcomes could produce a major victory, but it could also produce an unacceptable outcome. Again to quote Churchill:

“The chance of that happening [a British loss] may not be great, but if that happens, it could cost us the whole war.”

The strategy was to stay alive and play the long game—Not to make some grand, heroic strike.

You should apply a similar strategy with investing as well.

This week we were talking to a room full of current and former Intel employees about “Navigating the Financial Transition to Retirement.” Part of this presentation includes a review of common mistakes we see people make and ideas for avoiding them. One of the mistakes, that we see all the time, is over-concentration in one stock or sector. (See: 6 ways to diversify)

But someone asked the question, what is too concentrated? How do I know if I’m too concentrated?

Instead of some generic rule of thumb (e.g., no more than 10% or 15% in an individual security) here’s the real definition: If a major loss in your concentrated position breaks your financial plan, you are too concentrated.

If you can’t survive the position going to zero, or if you have to drastically reduce your financial priorities, it’s time to diversify. You don’t want to bet your goals, objectives and financial priorities on the back of one individual stock.

Because, just like with the variability of outcomes the British Navy was dealing with in World War I, investing in concentrated stock positions has quite variable and often catastrophic results.

From a 2014, J.P. Morgan whitepaper titled “The Agony and the Ecstasy: The Risks and Rewards of a Concentrated Stock Position,” comes the following:

“Around 40% of all stocks experienced catastrophic declines, when defined as a 70% decline from peak value with minimal recovery.”

And later:

“Remember, we are not talking about temporary declines during the tech boom-bust or during the financial crisis, but large, permanent declines that were not subsequently recovered. Technology, Telecom, Energy and Consumer Discretionary had the highest loss rates.”

Their conclusion (emphasis mine):

“This [a 70% decline] is a subjective cutoff point; many concentrated holders would see smaller permanent declines as equally unacceptable, and whose risk should be mitigated. The outcomes based on a variety of thresholds suggest that for many concentrated holders, diversification should be a central part of wealth management planning.”

Just as Churchill regarded it as intolerable to risk the entire outcome of the war on a highly variable outcome, betting your financial future on a concentrated position should be equally unacceptable. The J.P. Morgan study tells us that with stocks, the risk of a “catastrophic loss” is nearly equal to a coin flip. No one I know would bet their retirement on a coin flip, and yet, by being too concentrated many do just that.

Instead of tying your financial future to the fate of some company, diversification keeps us alive long enough to win the war. Or as Churchill famously stated after the 2nd World War,

“Today we may say aloud before an awe-struck world, ‘We are still masters of our fate. We still are captain of our souls.”

Click here for disclosures regarding information contained in blog postings.

Cordant, Inc. is not affiliated or associated with, or endorsed by, Intel.