In this post, we’ll outline everything you need to know about diversifying a concentrated stock position. We’ll cover what is too concentrated, the benefits of portfolio diversification (and the drawbacks), plus provide some tips on managing taxes.

In our conversations with Tech professionals, we’ve learned that most know they should diversify their portfolio. But they don’t know how to start.

After an IPO or a long career of accumulating shares in their employer via equity compensation, they’ve ended up with a significant portion of their net in a single stock. This position, rightfully so, leaves them nervous.

This is, as you would imagine, a good problem to have. You’ve built significant wealth, but due to a host of reasons, it’s not obvious how or when to make a change and diversify this position. In this post, we’ll give you an idea of where to start, beginning with what is considered a concentrated stock position.

What is a Concentrated Stock Position?

We are often asked some version of the question, how much of one stock is too much? And while there are various rules of thumb, the real answer is that it depends.

It Depends on Your Goals

How concentrated is too concentrated depends on your financial goals and the amount of risk that you’re willing to take on to achieve them.

Consider someone younger with financial goals that are significantly more ambitious than their current net worth could support. In this case, it may make sense to be more concentrated in an individual company as that position gives them a lot more upside.

But there are no guarantees that this extra risk will work out. In fact, as we’ll see later, the odds are stacked against you, but there’s a chance for a home run with concentration.

On the other hand, the closer you get to being able to fund your financial desires with your current net worth, the less it makes sense to make big bets on any individual outcome.

A Rule of Thumb

If you do any googling on this topic, you will quickly find that most professionals recommend a maximum of 10-15% as a rule of thumb for how much your company stock should make up of your total investments.

This is a helpful starting place, but the right answer for you will vary based on factors specific to you—your age, risk tolerance, other assets, spending level, life expectancy, etc.

Another way to look at it is not in terms of a recommended maximum percentage but in terms of the downside risk you’re willing to take on.

The Real Definition

Instead of some generic rule of thumb (e.g., no more than 10% or 15% in an individual security), here’s what I consider the real definition of what is too concentrated:

If a major loss in your concentrated position breaks your financial plan, you are too concentrated.

And before your think that could never happen to your stock or your employer, consider that it’s a very real possibility when holding individual stocks. According to a 2014, J.P. Morgan whitepaper titled The Agony and the Ecstasy: The Risks and Rewards of a Concentrated Stock Position,

Around 40% of all stocks experienced catastrophic declines when defined as a 70% decline from peak value with minimal recovery.

When looking at this by sector, Tech companies fare even worse than the average sector, with 57% experiencing a “catastrophic” loss over the period studied.

Sure, your company might be different, but are you comfortable risking serious money with those odds?

If you can’t survive the position going to zero, or if you must drastically reduce your financial priorities, it’s time to diversify. You don’t want to bet your goals, objectives, and financial priorities on the back of one individual stock.

So now that we’ve defined “too concentrated” and when to consider diversifying a portfolio, we need to understand what it means to build a diversified portfolio.

What is Portfolio Diversification?

Portfolio diversification is limiting the exposure in your portfolio to any one asset. Essentially, it’s the old adage of not putting all your eggs in one basket.

For example, if you own multiple stocks from different companies in your portfolio, you will be less impacted by anything (good or bad) that happens in any one company. By the same token, even if you own stocks via a diversified fund that tracks an index, like the S&P 500, your portfolio is very much tied to the overall health of the economy. In the event of a recession, the value of this position will likely fall significantly. Bonds, cash, or stocks from outside of the U.S. would help to diversify the position.

Spreading the risk in your portfolio across various risk factors helps create a smoother ride.

It’s been said that true diversification means always hating some of your investments. As a result, you never hate your portfolio.

3 Benefits of Portfolio Diversification

The main benefits of portfolio diversification are to reduce risk, reduce the volatility of your portfolio, and improve returns.

Let’s look at each of these benefits and the main drawback to diversification.

1. Risk Reduction. This one is pretty intuitive. Any investment in one individual company, country, or asset class is going to be overwhelmingly impacted by the risk factors affecting that asset (both good and bad). By spreading your bets across various stocks, asset classes, and countries, you reduce your risk to anyone specifically.

2. Reduce Volatility. Volatility isn’t the same thing as risk exactly, but they’re related. Volatility is bad for a couple of reasons. First, when it comes to investing, volatility is like speeding. The more volatile your portfolio, the more likely you are to decide to take some action that’s detrimental to your success—one that causes you permanent harm.

Speeding alone does no permanent harm to yourself or your vehicle (just like volatility in and of itself doesn’t damage your portfolio—it’s not a permanent loss). However, unless you’re a professional race car driver, this behavior seriously elevates your risk of getting in a wreck. Your margin for error decreases, and you’ve increased the odds of making a mistake.

Next, if you’re regularly withdrawing money from your portfolio, as you will in retirement, higher volatility means a lower withdrawal rate.

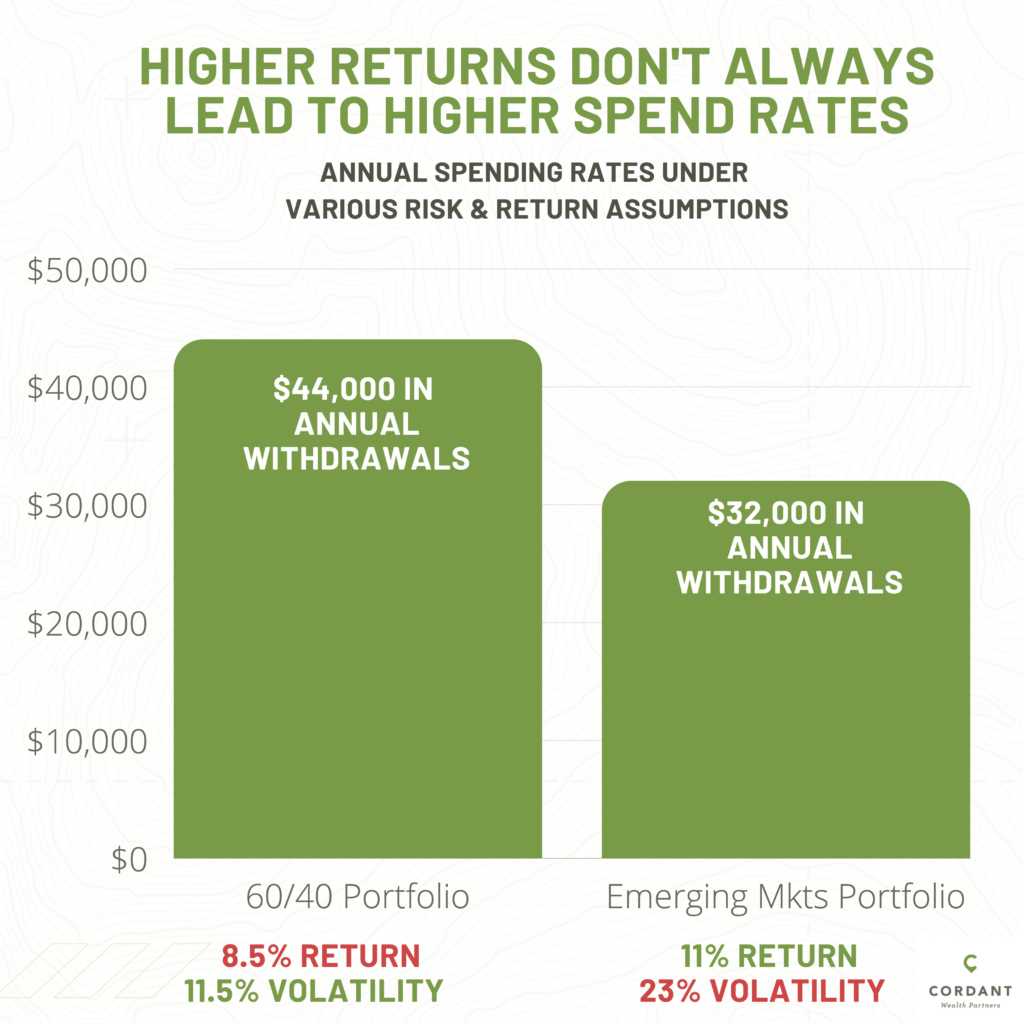

We’ll look at two examples. In both, we assume a $1 million portfolio and a thirty-year time horizon. In the first example, we use the historical risk and return assumptions of the classic 60/40 portfolio—around 8.5% annual returns with an 11.5% standard deviation. In the second example, we invest in stocks only. To drive home the point, we use Emerging Market stocks which have a higher potential for growth but also much higher volatility (roughly 11% returns with 23% volatility).

Despite the over 2% higher annual returns on Emerging Market stocks, we find our 60/40 portfolio has a higher safe withdrawal rate supporting $44,000 in annual withdrawals (versus about $32,000 for a portfolio that’s 100% invested in Emerging Market stocks.

3. Improve Returns. This benefit is a bit counterintuitive, but diversification can help here too by making sure you don’t miss out on the winning stocks or areas of the market.

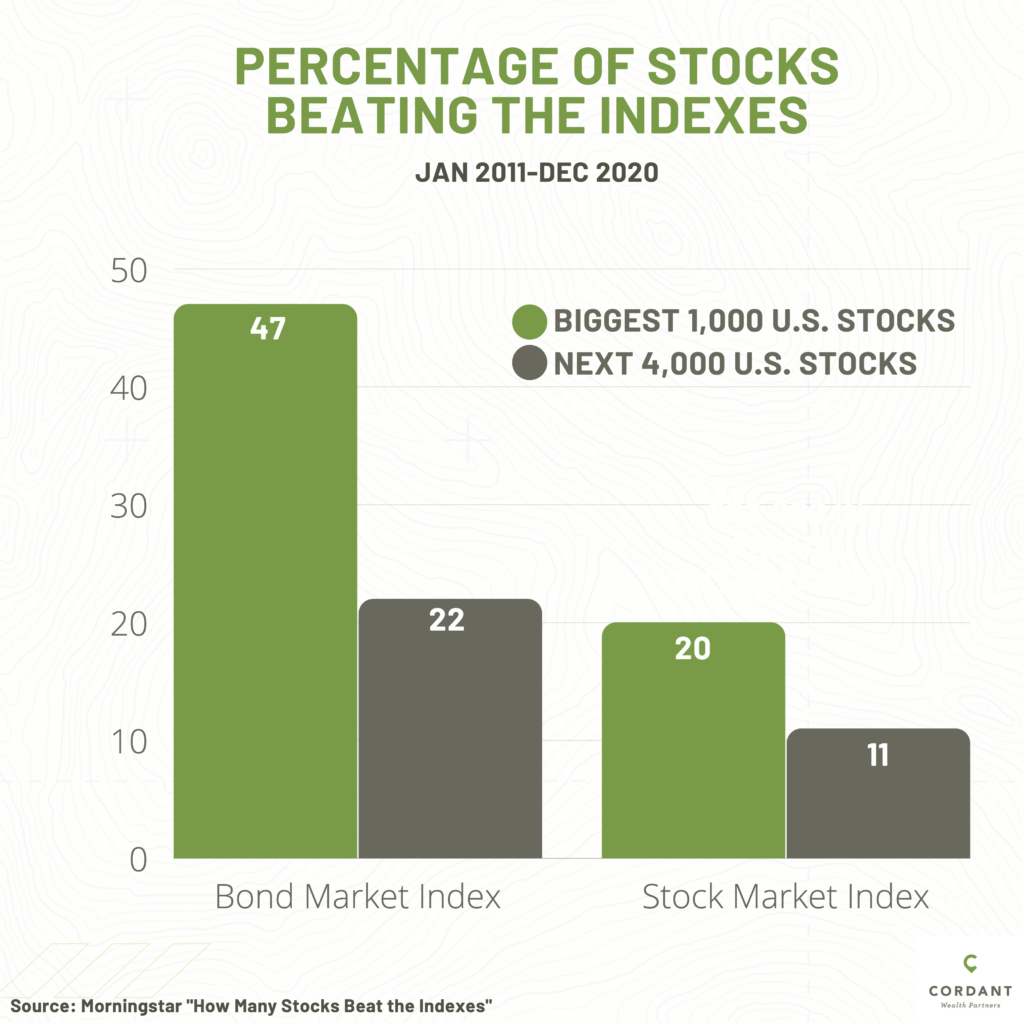

Research from John Rekenthaler at Morningstar showed that for the decade concluded in December 2020, only 20% of the largest 1,000 stocks had a higher return than their benchmark index. What this means is that if you’re holding a position in your company stock, your odds are only 1 in 5 of beating a broadly diversified index and only about 1 in 2 of even outperforming bonds.

Your odds are even worse if the stock you are holding isn’t one of the 1,000 largest companies in the U.S. stock market.

Main Drawback of Portfolio Diversification: No Lottery Tickets

Just as lottery tickets are still popular despite their odds, individual stocks, while not expected to beat the market, do provide the chance for a home run…

Concentration might provide a path to get rich, but it’s not a great way to stay rich.

And even if you do identify the right lottery ticket, sticking with it can be hard. As Michael Batnick points out, Amazon has been one of the best stocks in the market since going public in 1997. Its annualized return of 35% per year since IPO is unbelievable.

But to get those unbelievable returns, you’d have to endure unbelievably frequent drawdowns. Quoting Batnick:

Some of the losses Amazon has experienced along the way have been totally insane. It fell 15% in just three days 107 different times, it has lost 6% in a single day 199 times, and it fell 95% from December 1999 to October 2001.

Amazon has had a double-digit drawdown each year since going public and a 20% drawdown in 16 out of 20 years. The average Drawdown is -36%.

His conclusion is appropriate “Just because you take big risks, that does not mean you’re entitled to big rewards.”

How to Diversify? The 6 Types of Diversification to Include in Your Portfolio

Now that we’ve identified what we mean by a concentrated position and are familiar with the concept of diversification and why it’s important let’s take a look at how to build a diversified portfolio. There’s more to consider than just owning a handful of stocks or even stocks and bonds.

Here are six forms of diversification to include in your portfolio.

#1. Individual Company Diversification

It’s now easier than ever before to get a diversified allocation to stocks through a bevy of different index funds. This wasn’t always the case. In the ’50s, Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz demonstrated a portfolio’s risk dropped considerably as additional stocks were added to the portfolio—even if the individual stocks were all of equal risk. More recently, research by Longboard Asset Management revealed that over the period from 1983-2006, nearly 2 in 5 stocks actually lost money (39%), almost 1 in 5 lost at least 75% of their value (18.5%), and 2 in 3 underperformed the Russell 3000 index. Furthermore, the best 25% of all stocks over this period accounted for nearly all the gains.

Source: Longboard Asset Management

#2. Industry Diversification

Just like getting a mix of individual companies is an important way to diversify your portfolio, having a balance across the multiple different industries in the economy is important too. It’s especially important to remember to diversify away from the industry with which you are most familiar. For example, just like with the home country bias, people also tend to overweight their home industry. The chart shows that those living in the West tend to overweight Technology, as many are familiar with the tech companies based here or are directly working in the industry. The Northeast favors Financials, the Midwest Industrials, and the South, Energy.

The point is, just like with individual company stocks, it’s not healthy to overweight an industry that you are also counting on for your paycheck or regional economic health.

Source: JP Morgan Guide to the Markets December 31, 2015

#3. Asset Class Diversification

Different assets (Stocks, Bonds, Cash, Real Estate, Commodities) are going to perform differently in various economic environments. For example, during an economic recovery stocks will likely perform well, while in a recession, bonds provide protection. Commodities, TIPS or cash, can protect against the forces of inflation, while during a deflationary environment, long-term bonds are often the best investment.

#4. Strategy Diversification

Within asset classes, there are different strategies to get the exposure—many of these different strategies (also called factors, risk factors, smart beta, etc.) have been shown in academic research to deliver superior returns over time versus a market-cap weighted index. But, this outperformance doesn’t happen every year, and there can be long periods of underperformance. For most, the best approach is a mix of these factors (Value, Small-cap, Momentum, High Quality, etc.) with the realization that you won’t have 100% allocated to the hot strategy but that you also won’t be 100% committed to a strategy that’s lagging.

#5. Geographic Diversification

Again, most investors have a “home country bias,” preferring the stocks of companies based in their home country or region. However, the research also shows a benefit to diversifying internationally. For example, think about the performance of the Japanese stock market since its 1989 peak. As author Jonathan Clements wrote:

What if the U.S. turns out to be the next Japan? It strikes me as improbable. But in the late 1980s, when Japan’s economy was the envy of the world, the subsequent bear market would also have been considered wildly improbable.

My contention: If you’re going to invest heavily in stocks, you should consider allocating as much as 40% to foreign shares, so you aren’t betting too heavily on a single country’s stock market. I don’t know whether that will help or hurt returns. But it will reduce risk—and potentially save you from financial disaster.

Just like with asset classes or strategies no one economic region is going to consistently outperform. Best to have a mix.

#6. Time Diversification

Time diversification is essentially spreading out the timing of your investment. In the case of a lump sum investment or the execution of a diversification plan, this helps to minimize the risk of bad luck timing. If you’re still contributing to your investment accounts, Dollar Cost Averaging can reduce the impact of poor investment behavior (a lack of discipline) or unlucky timing. While the research shows that around 70% of the time, investing a lump sum is better than investing it over time, dollar-cost averaging or any rules-based, disciplined approach can lead to better investor behavior and, therefore, better investment results.

How to Build a Diversified Portfolio: A Case Study

At this point, we’ve defined a concentrated position, reviewed the concept of portfolio diversification, and introduced different ways you should think about diversifying.

Now let’s pull it all together and walk through an example of the steps in building a diversified portfolio, using the scenario below.

Scenario:

Susan, 55, has spent her entire career working and investing in the technology industry. As a result of diligent savings plus RSU compensation over her career (with no thought given to diversifying these shares along the way) and the recent IPO of her current employer, her portfolio looks as follows:

- $2,500,000 in three individual stocks (via RSUs) with a cost basis of $1,500,000.

- $1,000,000 in her current company via the recent IPO. Cost basis is $200,000.

- $1,500,000 in her 401(k) that’s invested 100% in U.S. Large Cap stocks.

Susan would like to retire in the next few years and is uncomfortable with the concentration and risk in her portfolio but is afraid of the tax bill that will come with selling.

Step 1: Identify Objectives and Constraints

Through a series of conversations, Susan identifies a few objectives and constraints:

- She would like a high probability of her portfolio funding her lifestyle over the next 40 years.

- She would like to continue to hold at least $500k total of the three individual stocks acquired via RSU’s.

- She would like to gift $250,000 to charity.

- Otherwise, she would like to build a portfolio that optimizes for #1.

Step 2: Identify Target Risk Level & Ideal Portfolio

Based on #4 above, with the help of her advisor, Susan is able to determine that a diversified core portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds (outside of the RSU stock that she will continue to hold) is able to support her annual spending target of $200k per year (adjusted annually for inflation).

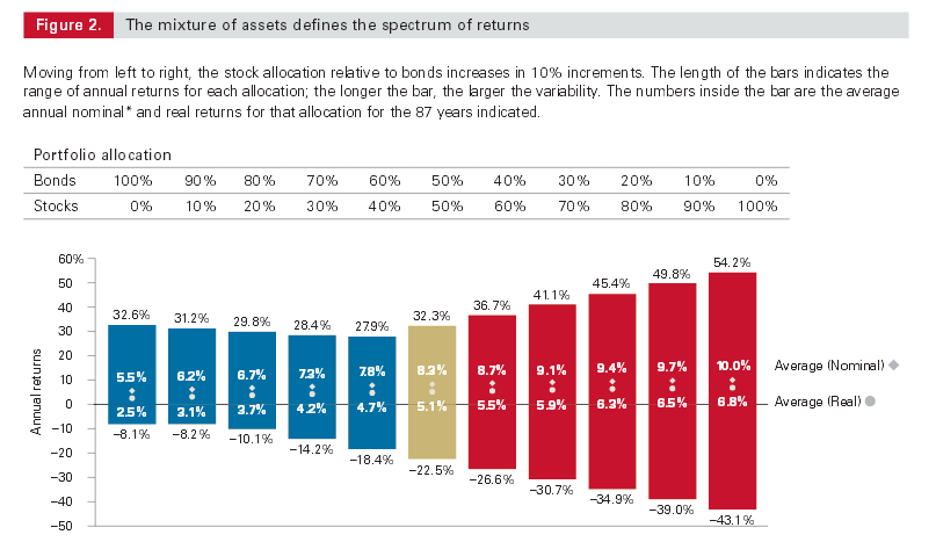

As can be seen in the chart below from Morningstar, the higher the allocation to stocks, the higher the potential for returns, but with that comes more risk.

Source: Vanguard

Because Susan doesn’t have legacy goals beyond the four listed above, she is comfortable owning bonds to increase the probability of hitting her goals—even though she knows she’s giving up some of the upside.

Step 3: Manage Taxes

Now that the target is identified, the hard work of moving to the target while minimizing taxes begins. Again, Susan works with her advisors, who, in coordination with her CPA, develop the following plan.

- Gift $250k of the IPO shares to charity as these are the lowest basis shares. Susan sets up a Donor Advised Fund (DAF) that allows her to get the tax benefits of the donation today while she is in a high tax bracket, but is still able to immediately diversify the position and gift the money to charities of her choice over time.

- Move $1 million of the RSUs into a Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT). Like DAFs, CRTs are a potential strategy to make a one-time charitable contribution and receive the tax benefit in year one and maintain the ability to distribute the funds down the road. However, unlike the DAF strategy, CRTs can be set up to provide income to the donor (or their beneficiaries) over their lifetime. A CRT works as follows:

- Individuals place assets (cash, publicly traded securities, real estate, some private company stock) in a trust;

- A tax deduction is taken in the year the CRT is setup;

- You, or your beneficiaries, receive an income stream from the assets;

- And lastly, based on a pre-defined timeline or the death of the last beneficiary, the remaining balance of the CRT is distributed to the charity of your choice.

- For the remainder of Susan’s equity allocation (around $1.5m), she elects to use a Direct Indexing Solution. While similar to Indexed Mutual Funds or ETFs, in that they are low costs and diversified, the Direct Indexing Solution allows Susan to customize her portfolio and manage taxes at the individual level. For her, this means that she can manage around the RSU positions she wants to continue to hold by not owning any more of these stocks and reducing the exposure to the Technology sector, as it’s already held in other parts of her portfolio. Additionally, she is able to manage the tax impact and spread out the gain over time, and offset some gains through tax-loss harvesting in the account.

- Lastly, because her 401(k) is not subject to taxes today, Susan is able to sell the equities in that account and buy bonds to round out the allocation. Using what’s known as Asset Location, she is able to shield the income from the bonds by holding them in her 401(k).

Step 4: Enhance Returns

The last step is to make sure her overall allocation is balanced so as not to miss out on the areas of the market that are generating returns.

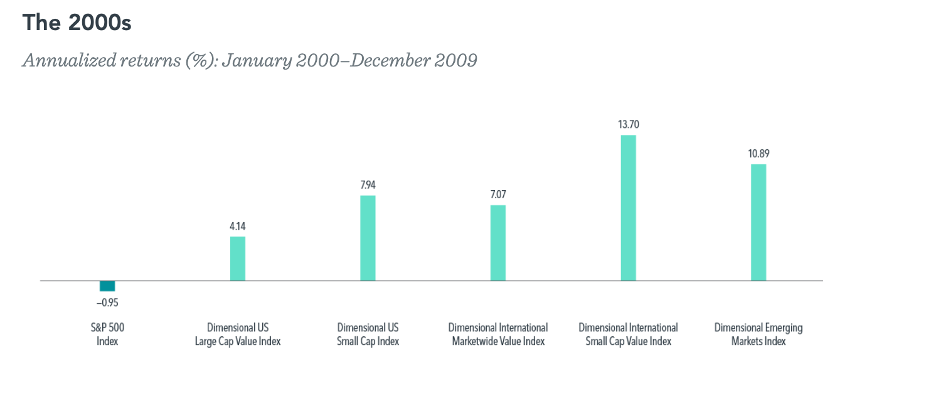

For example, in the “Lost Decade” of the 2000s in the U.S. Stock market, there were areas across the globe that made money even while the most common measure of U.S. stocks, the S&P 500 index, did not.

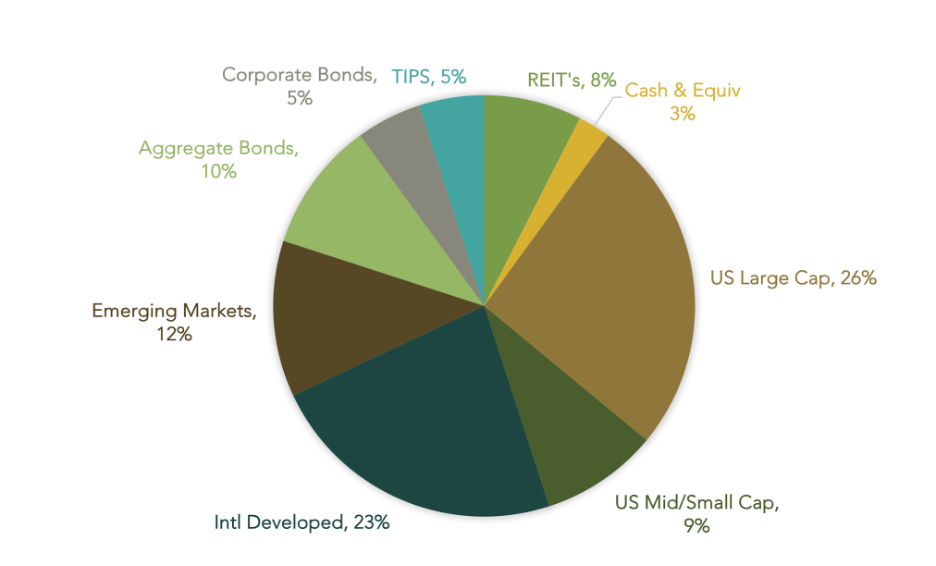

Her diversified portfolio that ensures she is balanced at the company, industry, assets class, strategy, and geographic level might look something like this: