The market downturn this past month reminded me of this podcast that I recently listened to while driving home and the question that followed. During the podcast, Cliff Asness, a well-known hedge fund manager and founder of AQR Capital Management, discussed investment strategies that are based on the historical data and in theory, are very appealing. He joked however, that due to the volatility of the strategy, or just how different than the rest of the market performance would look, it would take having the disposition of a Vulcan (Mr. Spock’s Alien Species in Star Trek) to stick with. He cautioned, “the better strategy you can’t stick with is not the better strategy.” His point being that with any long-term investment strategy, the benefit is only realized if you can stomach the periods where it doesn’t perform well or performs differently than your expectations. The question that followed for me was, “how do I know what I can stick with?”

The fact that I was driving home and sitting in traffic when as I was listening to the podcast made the statement really hit home for me. Here’s why: My wife uses the app Waze for driving directions almost every time she is behind the wheel. If you’re not familiar, the app uses crowd-sourced data to calculate the shortest route to a desired location. I spent a long time doubting the app actually provided a shorter route because it would send me down a road with 10 stop signs or suggest turning left onto (or crossing) a busy street without a stoplight to make the turn easy. Frustrated, I would say to my wife, “No way this is faster!” But, over time we have had occasion to test it–traveling from the same places to the same destinations in different cars where she uses the app and I don’t, and she wins every time (her winning seems to be a recurring theme in life, but that’s another blog post). Finally, I accepted that it is faster to use the app.

However, despite my acceptance that it’s faster I still either ignore the app or worse, I start by following the directions only to abandon the suggested route at which point I’m even worse off. Why do I abandon the directions? Because I get too frustrated! Most of the time, I would rather drive slow on a heavily trafficked street than deal with stop signs, pedestrians, and bicycles on side streets. I also get anxious when I know I am going to have to turn left on a busy street without a stop light. The benefit of a couple extra minutes just isn’t worth the pain and anxiety for me. My wife, on the other hand, isn’t fazed by the obstacles in the route. For her, there is no reason not to recoup a couple minutes in her day that would have been lost to traffic. To apply Mr. Asness’ words to my driving situation: “Waze is not a better strategy for me, because I can’t stick with it.”

As an investor, it is crucial that I can stick with the implemented strategy. As an advisor, it is likewise crucial that I don’t recommend a plan to which I know a client will not be able to adhere. However, gauging the amount of turmoil one can handle is tricky.

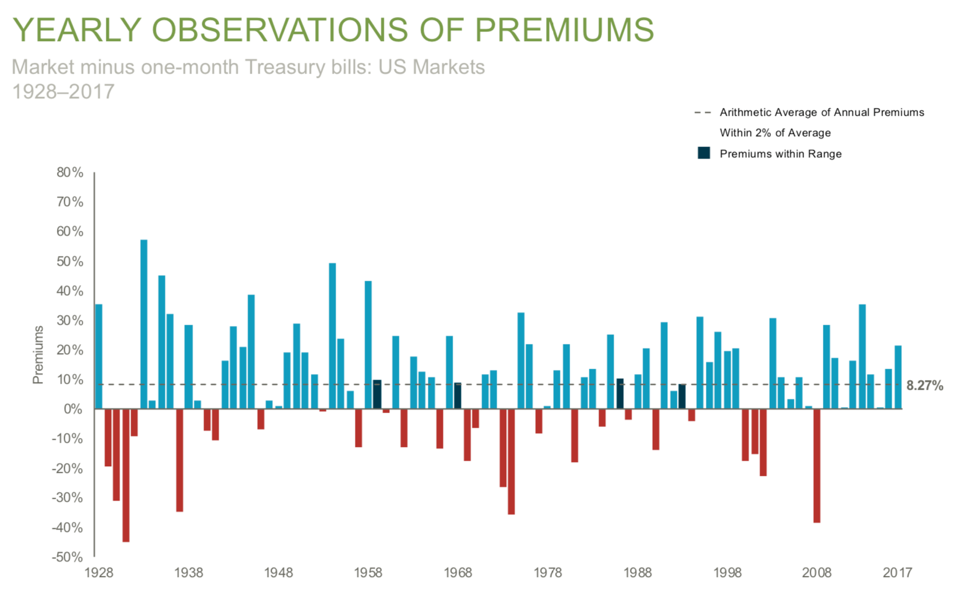

Take, for example, a decision as simple as investing in the US stock market vs. 30-day US Treasury Bills. Historically, those who have chosen the US stock market have enjoyed on average an 8.27 percent premium over that which would have been realized from one-month of US Treasury bills. The following charts the premium (or lack thereof) year-to-year:

Source: Dimensional Funds

That 8.26% premium on average is appealing but, as the chart demonstrates, you don’t have to dive deep into the annals of history to see what you have to put up with to get that premium: – 40% underperformance in ’08 and three consecutive years of less-than -10% underperformance from ’00 to ’02 are two very recent examples. Just as my wife doesn’t mind edging out to stop traffic and turn left on to a busy four-lane street at 6 PM to save a couple extra minutes on her commute, there are investors who can stomach losing 40% of their portfolio in one year if it means a better outcome long-term. However, there are many investors who can’t. Each individual has to decide how much downside and volatility they can handle.

I think we should all use these last couple weeks as a gut-check. The difficult part about knowing what you can stomach, is that sometimes you just don’t know until you’re in it. An example back to my driving analogy: the left turn on a busy street may not cause you any anxiety until you actually have to make it. The best indicator of your tolerance for risk is real experience. Many of us that experienced the late 90’s and ’08, remember what that felt like, and can use that experience as a gauge. But for others, it may be that life was different then—you were too busy at work or at home, and retirement way too far away for extreme markets to have been blip on your radar.

No one can reliably tell you where markets are going to next based on a few weeks of data, but we can use history to inform decisions. Allow this recent downturn period to inform your plan, and in doing so increase the likelihood that it is the best one for you.