In Part 1, I explained at a high level the mechanics of how Cordant generates a paycheck for clients from their portfolios in retirement.

In this “Part 2,” I want to follow up with examples of how we evaluate other available strategies and why we use the “total return” approach described in Part 1.

We are continually researching and evaluating new strategies, and this cursory review of a few of them is in no way meant to be exhaustive, it’s meant to highlight at a high level how we evaluate a strategy. In fact, it’s just the tip of the iceberg so to speak of strategies that are out there.

That being said, when we evaluate strategies for generating cash in a portfolio that will translate to spending money for the client, we are considering two overarching questions:

- Is the strategy optimal financially? (In other words, does implementing the strategy translate to more money for the client over the long term?), and

- Is it a strategy we can implement and that the client can stick with?

The first question is one that can be answered in a number of ways, and we are not going to review all of those methods here (there are books dedicated to this topic alone). The most common evaluation method is to look at the strategy’s ability to improve the maximum a client can withdrawal from their portfolio over time without running out of money. This is known as the maximum safe withdrawal rate, and it should be noted that focusing on maximum withdrawal rate alone has numerous short-comings which we have previously written about. This first question, regardless of how you answer it, eliminates strategies for obvious reasons: i.e., those strategies that equate to less money for the client, get eliminated unless their valuable benefits make the trade-off attractive.

The second question may involve less analysis but often involves more nuance. For example, the strategy may improve maximum withdrawal rate over a client’s life, but make the client feel like they’re taking on more or less risk. Or, maybe logistically, it’s just a lot of work on the client’s end to implement. In order to illustrate this evaluation process and how strategies are weeded out, I think it is helpful to review a few popular (or at least often written about) strategies, and discuss how we evaluate them:

Strategy Example 1: The Income Approach

This method is probably the most straight-forward: invest in income generating assets which produce a steady stream of cash flows. As those cash flows are received, transfer them to the client’s account for spending.

As the graphic depicts, it’s a simple method by which income from one’s investment assets are deposited in a bank account and spent. The approach appeals to many because of its easy setup. Further, from a risk perspective it is attractive because the income from the assets (particularly if it’s mostly bonds) is dependable, consistent and tangible. However, as my colleague Scott Gerlach previously pointed out, there are two big problems with this approach:

- You are leaving out a huge number of investment opportunities. By focusing solely on bonds and dividend paying stocks, your portfolio neglects massive chunks of the market and can reduce your returns and increase risk by leaving your portfolio overly concentrated.

- The next issue with an income approach is that yield is quite expensive in the current market environment. Because yields on bonds aren’t what they were a decade ago, you need substantially more in assets to generate the necessary level of income.

Bottom line: this approach doesn’t survive the first evaluation question above as it’s not financially optimal nor does it survive the second. This is an especially difficult strategy for clients to implement for two reasons: First, the size of investment necessary for it to produce sufficient income; and second, the loss of upside. If the client proceeds with this strategy, they are likely to feel like they are missing out when markets are up. Unless the client values and is willing to pay for security and consistency at additional upside costs the strategy doesn’t make sense.

Example 2: The Bucket Approach

Despite his issues with the SEC, probably the best-known bucket approach is Ray Lucia’s “Buckets of money” approach. I recognize I am likely simplifying the strategy here, but most iterations of the approach essentially involve moving your investments into three buckets:

- The first bucket contains safe-money investments, enough to fund seven years of withdrawals;

- The second bucket contains moderately safe investments, enough to refill the first bucket for another seven years when it empties; and

- The third bucket contains higher risk assets, typically equities, to refill the first two buckets when they are both depleted after approximately fourteen years

I think the benefit to this strategy is in its simplicity. Funds to be used in the short term are in a safe bucket while funds to be used further in the future are allocated more aggressively. The strategy reminds me of how my grandmother used to keep cash in envelopes. There was an envelope for groceries, for charitable donations, for eating out, etc. Anywhere she was going to spend her cash had an envelope. She liked knowing she had cash “bucketed” for specific purposes. She also liked this method because when her “eating out” envelope was depleted, she didn’t eat out until next month—it was a simple way to not go over budget. My point is that for many this strategy will survive the second question above in that it is simple to implement and likely easy for a client follow.

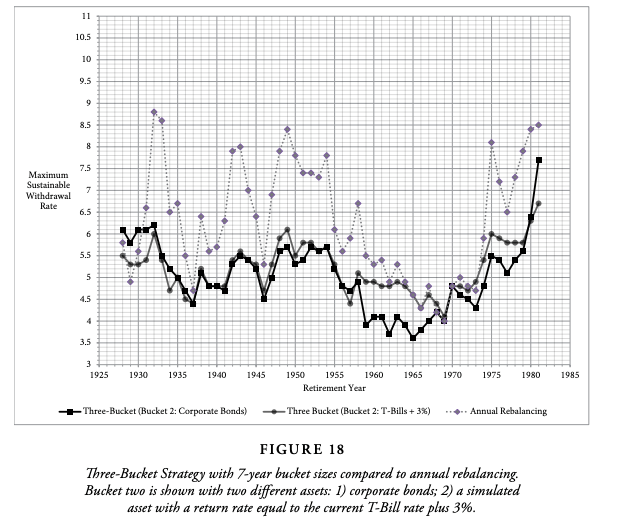

However, the strategy fails to survive the first question as it does not often prove financially optimal. There has been a great deal of analysis performed on this method but this chart from Michael McClung’s book, Living Off Your Money, highlights this well. In one of the several analyses he performed, he looked at how the maximum sustainable withdrawal rate for two versions of the bucket approach would compare to what he calls “Annual Rebalancing” (essentially a simplified version of our “total return approach” described in Part 1 except that cash for the year is raised once annually). Here are the results graphed and you can read about the details of the comparison in an excerpt from the book here:

As you can see, in the majority of starting retirement years, the three-bucket approaches modeled would not have allowed for as high of an annual rate of withdrawal as annual rebalancing would have.

The takeaway from this is that history suggest this approach means the client would be able to spend less from their portfolio. Therefore, unless the peace of mind that having money in buckets like this, is truly valuable to the client; we would not implement this strategy.

Example 3: Guyton/Klinger Decision Rules Based Approach

Since, in the first two examples we looked at income generating strategies that are not as financially appealing as our Total Return approach, I wanted focus on one that could be considered more appealing financially, but that we don’t implement.

This approach was proposed by Jonathan Guyton, principal of US firm Cornerstone Wealth Advisors, with the help of computer scientist William Klinger. I am not going to detail the approach in this post, but here is a nice summary of how the strategy is implemented. Ultimately, Guyton and Klinger propose that by following some simple rules that will mean adjusting spending rates based on inflation and the prior year’s portfolio growth or loss, one can increase the amount they can spend from their portfolio over time. And, back tests and other modeling have suggested that the strategy does mean more money over time.

However, the issue with the strategy comes in addressing question two at the beginning of this post: It fails because it would be difficult for most to stick to and follow. Most of our clients do not spend the same amount every year nor do they plan to. They want confidence they can have big spend years in the years they plan to spend more regardless of the prior year’s return.

Cash flows are usually lumpy. Decisions to fund a grandkids education or help with the down payment on a house mean that spending is not the same year to year. For many, a strategy like this is too confining and what makes it worse is that if one abandons the strategy for even a year the whole benefit to the approach may as well have been thrown out the window. One could be worse off for implementing it in the first place.

Back to the Total Return Approach

For our clients the Total Return Approach survives both levels of scrutiny. It makes financial sense and we along with our clients can implement and stick with it. This is not to say, however, that what is right for one is right for all. While we currently employ this approach across clients the decision to employ is not made as such. It’s a decision that should be and is made on an individual basis.