Harvard’s Endowment has been making headlines recently due to its $2 billion investment loss in the fiscal year 2016. And the Crimson (the student newspaper) is up in arms about this “unacceptable” loss.

From their article The Urgency of the Present come the following gems:

Harvard Management Company announced a $2 billion loss for the fiscal year 2016.

Let’s not mince words: this is unacceptable.

Now, a $2 billion losses certainly catches attention and grabs some headlines, but it’s only a major loss in dollar terms. Because of the endowment’s size (a good thing for Harvard) it’s not a major loss in percentage terms as the paper admits:

“…help to bridge this small (in percentage terms) loss.”

The editorial continues with some advice of sorts:

“We also recognize that we are not investment advisors. College students have no business telling seasoned analysts and managers where to invest the endowment. Instead, we wish to urge the administration to prioritize endowment performance before Harvard falls further behind peer institutions.”

From my vantage point this is a case study on how NOT to evaluate your investment performance. Let’s take a look at what we can learn from this example.

Don’t assess your investment performance

1. Over the wrong time frame

The student newspaper is up in arms over a one-year performance when the endowment has an investment mandate of considerably longer. From the university’s website, “Harvard’s endowment, the University’s largest financial asset, is a perpetual source of support for the University and its mission of teaching and research.”

Harvard defines its endowment’s time frame as perpetual, meaning lasting forever, or to use financial jargon, in effect for an unlimited duration.

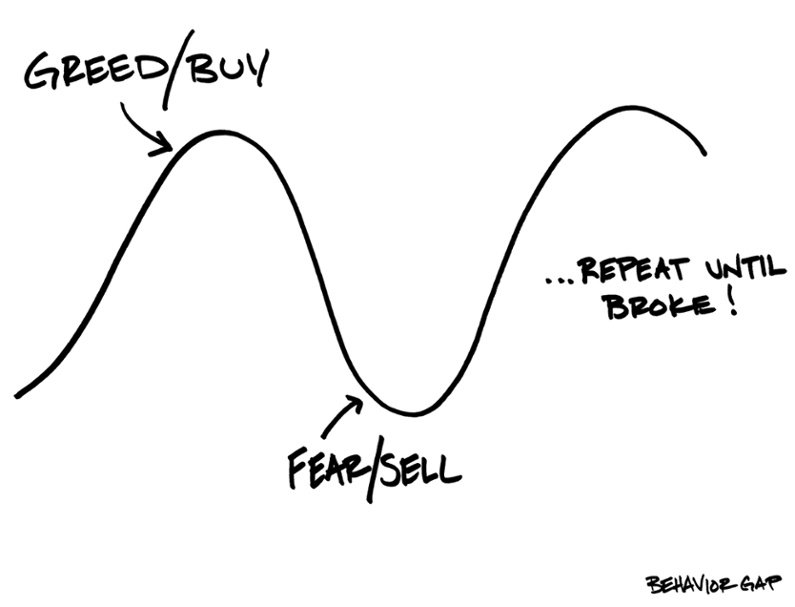

When your goals and objectives are in the long-term, it doesn’t help to assess performance in the short-term. This is a big reason why investors buy high and sell low…the opposite of what they should be doing.

2. Without proper perspective

A small loss is not only acceptable it’s a requirement of investing.

While a $2-billion-dollar loss might seem like a big one, for an endowment the size of Harvard’s this only represents a 2% loss. And how “unacceptable” is a 2% loss? Since 1926, the S&P 500 index has lost 2% or more in nearly one out of every four rolling 12 month periods. And yet over this period the index has compounded at 10% annually turning a $1000 investment into nearly $6 million.

No one likes a down year, but to increase returns by taking stock market exposure you have to be okay with the reality that it’s going to happen.

3. Expecting to outperform every year

No strategy is going to deliver positive returns, let alone outperform year in and year out.

Cambria Investment’s CIO Meb Faber in his great recap of Harvard’s recent performance makes the same point. He writes:

If you’re going to be an active manager, the whole point is to be different. Any investment approach will have years of under and outperformance. We examined how’s Buffett’s stock picks, despite beating the market by 5% a year since 2000 and outperforming 98% of all mutual funds, would have underperformed the market 8 of the past 10 years.

And without proper perspective, investors hop from hot strategy to hot strategy in a futile attempt to increase returns. Instead of preventing one from falling “further behind peer institutions” this lack of perspective creates the behavior gap that over time is a much bigger deal than a 2% loss over any one fiscal year.

Ritholtz Wealth CEO Josh Brown conveys the following story of how one of history’s greatest investors dealt with an investment loss. Here’s Josh:

As Nick Murray explains, Warren Buffett was down quite a bit that summer.

$6,200,000,000A very large sum of money, wouldn’t you say? Now what, you ask, does it represent?It is roughly how much Warren Buffett’s personal shareholdings in his Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. declined in value between July 17 and August 31, 1998. And now for the six billion dollar question. During those forty-five days, how much money did Warren Buffett lose in the stock market?The answer is, of course, that he didn’t lose anything.Why? That’s simple: he didn’t sell.

If Buffett was managing Harvard’s Endowment and lost $6 billion dollars, you could bet the student editorial board would demand something change. And yet, as he revealed, sometimes not acting is the right action to take.

Performance reporting is important, after all, it’s the third pillar of our approach (Plan. Invest. Report). It’s critical to close the loop and make sure your plan and investments are on track to achieve your goals and objectives. But, for performance reporting to be useful and not an exercise in the type of short-term overreactions exhibited by the Crimson editorial staff, a little perspective, and proper expectations need to get built into the process as well.

[1] As a proud graduate of not one, but two West Coast, state universities —go Beavs, go Vikings!—about as far as you can get from the hallowed halls of Harvard.

Since Jan. 1926 there have been 1077 rolling 12 month periods of which 244 have returned a loss of 2% or more.

Click here for disclosures regarding information contained in blog postings.

Cordant, Inc. is not affiliated or associated with, or endorsed by, Intel.